|

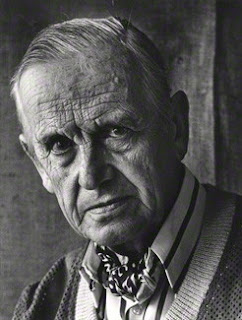

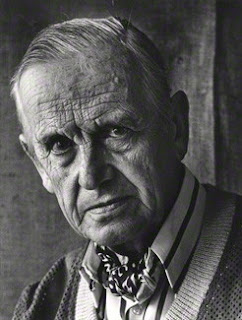

Graham Sutherland (1903-1980)

|

Death, development and rebirth are the cores of this visionary painter's artistic research. Whereas Francis Bacon innovated English art by disfiguring living (often human) shapes in the cage of the I, Sutherland's main result, through the horror of war he strove to depict, was probably the germinating of a portrait of an everlasting life which, even under a bombing sky, manages to keep his power of changing.

Nothing stops growing up, even in destruction, and the great quantity of vertical figures in Sutherland's pictures is the very evidence of his yearning for life and ascension to organic fulfillment. From this Londoner artist's point of view, life is an obscure, often monstrous energy animating the things/creatures, indifferently; however, in my opinion, considering his artworks as an inhuman, alien self-developing creature whose man is not but an asymmetric organ would be a great mistake.

|

Horned forms (1944)

|

Actually, in Sutherland's artworks man is always present. The eerie, sometimes horrific fusion of animal and vegetal elements (thorns, in particular, start growing up in his pictures of the 40s) is not but the symbol, I may say an icon, of human fear. Something "iconic" or even religious fidgets, relentlessly, in his shapeless, non human mixtures, since, by borrowing an expressionist struggle against matter, he uses nature to depict, indirectly, universal human feelings. His solemn, majestic figures may remind us De Chirico's metaphysics, but these two artists get to opposite sides: De Chirico never puts life in his silent landscapes, Sutherland always does.

|

| Thorn tree (1954) |

War, which Sutherland studied by a very close distance during his work as a "war artist", reduces life to some kind of "blob", to a chaotic mass of unpredictable evolution. His Heads series testifies his tendence to omit the human figure in order to speak about human life itself; as in his later religious subjects he painted for several churches (the figure of Jesus is both a quivering portrait of secular uncertainty and a powerful warning about universal sorrow), the tall, huge twisted columns of Three standing forms in a Garden, or, even more, of the majestic The origins of the land show us a world where human presence is an accidental, destructive as well, element of the vital evolution: differently from Bacon, who's obsessed with closed, narrow spaces, Sutherland prefers using large, open, empty landscapes, like settings of an imaginary prehistory, a churning universal birth where life is still a shapeless womb or, maybe, of an apocalyptic post-war planet where man trascended his fragile and dangerous form.

|

The origins of the land (1951)

|

|

Three standing forms in the garden (1952)

|

Sutherland is a fascinating scenario of regeneration and, in the meantime, a scaring suggestion of unpredictability of organic matter, and, consequently, of history. He wrote the poem of rebirth from the ashes, bestowing upon life, as well, an awe-inspiring dignity, regardless of the type of creature containing it. In his eyes, life is a whirlwind, an overwhelming tempest of colour which man cannot withstand: in his late works, you can notice colours turning deeper, shades more numerous, tones more soul-destroying; starting from the 50s, you can see his attention for psyche in his portraits and his unsettling animal-shaped figures, less plant-like, more tragic.

|

| Head III (1954) |

|

| Crucifixion painted for the Church of Saint Aiden, Acton (1961) |

At the end of his reasearch, maybe, we must see matter going back into the inside, in the tormented mind universe Bacon found in a cage: in the astonishing Sitting Animal we see, once again, mankind, the human loneliness, the monster-like condition of a self-devouring society, and this crouching posture, as a return into the Self, maybe meant, from Sutherland's point of view, the end of any compromise between reason and psyche.

|

| Portrait of Edward Sackville-West (1953-54) |

|

Sitting animal (1964)

|

Pictures are contained in: Sutherland, from the series I Maestri del colore, Fratelli Fabbri Editori, Milan, 1966.