|

| Blade Runner (1982) shows you perfectly how deeply, and how quickly, our views about future changed. If they're really going to release a second episode, I guess we'll see a totally different ensemble of futuristic elements, including, hopefully, monitors with a better resolution. |

I already know you'll disagree. Many of you are just thinking that several genres still have a lot of things to show in terms of style and innovation, that you were so moved or so amused by that comedy or that tragic story, that it depends on one's taste and perspective, that that movie with Leonardo DiCaprio made you cry, that you felt your bowels twisting with rage during all the bloody tortures in 12 years a slave etc. etc.

So, first of all: what does "interesting" mean in this post? It means realistic. And what do I mean when I say realistic? I mean weighty, rich and problematic in terms of study of reality, of scientific analysis; this doesn't have anything to do with amusement, special effects, emotion, actors' skills, Michael Fassbender's coolness and so on. Depicting reality is the very essence of art, and an artist is not necessarily an entertainer, and vice-versa. Moreover, art is not just emotion. In the aristotelian sense, art is imitation of life, and the fact our view of life is always limited and keeps changing through the history doesn’t mean art can afford to stop analyzing it.

Example: I LOVE Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), really; I mean, I could say it was epic, majestic, awe-inspiring etc., BUT it was not problematic: it didn't tell me anything about my reality, my world, the modern human's philosophical point of view etc. Reality keeps changing, and works of art show us the flowing of changing.

Second example: The Revenant (2015), the revelation, greatest film of that year, DiCaprio's best etc: personally, I couldn't stand that film, since, well, watching an almost three hours long picture with a man suffering, starving, stumbling, falling from mortal heights and miraculously rising up again, surviving just with his mind steadiness instead of (logically) dying for septicaemia and persuading a virtual bear not to kill him even after shooting it is not a very fulfilling experience (no, I'm sorry: the fact it was semi-autobiographical does NOT make it more special, and stop with the “woow, a true story” effect); BUT: this doesn't mean I cannot admire the actor's skill, the special effects, the soundtrack, the make up and all the technical elements which made this film a "nice thing to watch spending few hours of your life", but NOT what I call a work of art.

Example: I LOVE Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), really; I mean, I could say it was epic, majestic, awe-inspiring etc., BUT it was not problematic: it didn't tell me anything about my reality, my world, the modern human's philosophical point of view etc. Reality keeps changing, and works of art show us the flowing of changing.

Second example: The Revenant (2015), the revelation, greatest film of that year, DiCaprio's best etc: personally, I couldn't stand that film, since, well, watching an almost three hours long picture with a man suffering, starving, stumbling, falling from mortal heights and miraculously rising up again, surviving just with his mind steadiness instead of (logically) dying for septicaemia and persuading a virtual bear not to kill him even after shooting it is not a very fulfilling experience (no, I'm sorry: the fact it was semi-autobiographical does NOT make it more special, and stop with the “woow, a true story” effect); BUT: this doesn't mean I cannot admire the actor's skill, the special effects, the soundtrack, the make up and all the technical elements which made this film a "nice thing to watch spending few hours of your life", but NOT what I call a work of art.

So. Why sci-fi? Of course this genre changed a lot since its origins, and as you know genres grow more and more difficult to define: sometimes sci-fi means metal, hard silvery surfaces, laserguns, white aseptic rooms, but sometimes it just means a dramatic plot developing around one single futuristic element (The Astronaut's Wife [1999], Womb [2010]). Aliens are not that scaring anymore, and abductions are, at most, a cheesy horror happening (have you ever seen Extraterrestrial [2014]?) or a curious linguistic exchange (Arrival [2016]).

We cannot imagine things, obviously, by using the same fantasy as once: maybe you forgot, but Blade Runner (1982) was set in 2019; 2019, got it? Basically, according to Scott's cult masterwork, we are already using both perfect humanoid robots and monitors with a very bad resolution. Nowadays, instead, we (well, most of us) cannot even imagine what's going to be invented in the next two years, and our predictions about future society cannot be but murky (and often worrying).

And all of this notwithstanding, the chief philosophical and social problems of our time (starting from 2000, more or less) are faced and depicted especially by sci-fi; I very rarely found the same “weight” in other cases (and of course I’m not saying I didn’t enjoy any other films at all): sci-fi is pretty much the only genre which still “dares”, from time to time. I think this also happens because we said basically everything about all the rest, and cinema (as already happened to literature long time ago) is growing old.

“Late capitalism”, as someone defined this era, should be portrayed by expressing its decayment, but it’s quite easy to notice that most of the recently released films are just… pathos-oriented. Everything is pathos, and people comment like this: "Oh nice... but a little sad!" So, when I say sci-fi, I mean, in general, films with at least one sci-fi element: the film itself can be either a romantic story, or a post-apocalypse story, or a space journey, etc. It's impossible to be more precise.

“Late capitalism”, as someone defined this era, should be portrayed by expressing its decayment, but it’s quite easy to notice that most of the recently released films are just… pathos-oriented. Everything is pathos, and people comment like this: "Oh nice... but a little sad!" So, when I say sci-fi, I mean, in general, films with at least one sci-fi element: the film itself can be either a romantic story, or a post-apocalypse story, or a space journey, etc. It's impossible to be more precise.

|

| Cosmopolis (2012) is one of the rare not-exactly-sci-fi films dealing with decay of capitalism. Cronenberg's last film, Maps to the stars (2014), is another beautiful portrait of the "tiredness" of the rich class, stuck in its contradictions, and the relationship between the entertainment industry and the Western society. Cronenberg, where are you? We need your disturbing talent! |

The fact is that sci-fi still shows us aspects of reality which are worthy of a deep discussion - namely, which are problematic. They lead us to some kind of reflection about the development of human society, our main fears, our uncertain and scared perspective about the weakness of global economy, and they do so way more effectively than other genres. I believe that these films (beware: I'm not talking about ALL the films with this tag) may be the only films left which make us think, not just feel. There are very few exceptions lately.

In particular, our relationship with technology, space exploration and artificial intelligence still generates works which I wouldn't define just entertainment, regardless of their actors' popularity, their budget etc. Our way to imagine the future, of course, keeps changing, but since the human race seems to be particularly tired in this period, I'd say that sci-fi tries to imagine all the possibilities (and the complications) that humans could pass through this decay by becoming something more than human.

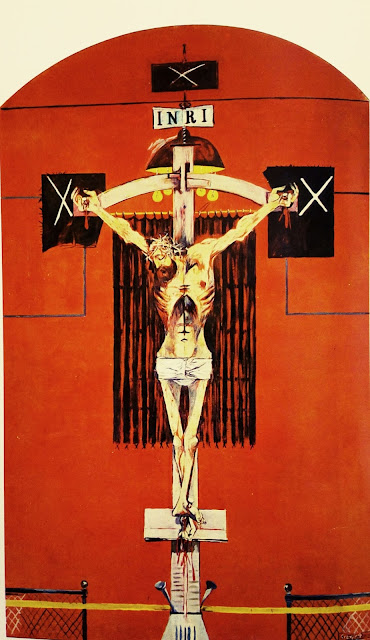

|

| British The Machine is an interesting sci-fi work about the possibility of recreating someone's appearance by means of engineering reconstruction, but also, and most of all, about the superiority of a robot mind which can absorb and quickly assimilate, once come to life, any kind of information, exactly like a child. The ending lets you understand this curious, innocent female android will be the first individual of the new (hopefully) peaceful race ruling the Earth. |

Probably, we're still not ready to transcend our physical form; we still have too many problems to fix: first of all, I guess, the death of our planet. But everything in our habits shows us that we cannot just be happy to focus on a career and keep saving money until death; not anymore. We can be many things, many people, in many places. Our synapses expand in all directions. We strive for a virtual life, because ours looks more and more narrow. We grew up in a technology-based society, and we must deal with it; art must deal with it.

I’m a little tired of hearing art being defined as “feelings”, honestly. Genetic augmentations, artificial intelligence, supercomputers are for sure more "interesting" (I won't use inverted commas anymore) than tear-jerking musicals set in a modern Los Angeles or battles against orcs for the reign of Azeroth (although battles against orcs are one of the thing I'm eager to watch after a standard working day).

I’m a little tired of hearing art being defined as “feelings”, honestly. Genetic augmentations, artificial intelligence, supercomputers are for sure more "interesting" (I won't use inverted commas anymore) than tear-jerking musicals set in a modern Los Angeles or battles against orcs for the reign of Azeroth (although battles against orcs are one of the thing I'm eager to watch after a standard working day).

|

| I won't talk about Gattaca (1997), a sci-fi masterpiece about future of eugenetics in a competition-based society, for two reasons only: first, I'm trying to focus on more recent works; second, it would be too difficult to me to stop writing, and I'd probably need an entire new post. But please watch it. You must. |

I want to make some examples of recent films that impressed me in terms of realism - according to the meaning I explained above. Let's begin from the best one: Ex Machina (2015). Finally, a beautiful dialectic fresco about the deep contrast between free will and predestination, humanity and machines, reasons and feelings. Apart from its brilliant visual effects, personally I don't know any better film about problems and doubts raised by modern conceptions about androids. Basically, you cannot guess, until the end, whether that beautiful female android has got human feelings or not; the spectator is led to think, not just to feel, and this is the main reason, of course, why this film is on the list.

|

| I think this film definitely deserves a place in the list of the best pictures about robots ever made; you must wait until the end in order to get what is the difference between human and artificial intelligence; which is dialectically explained. Art itself, painting in particular, is mentioned in the film, connecting spontaneity and artificial program in an exquisite dialogue. |

Ex machina speculates through and through, as well, about the idea of spontaneity, which is the root of human unpredictability and of human art too. Just because we think about a painting to create by means of a mathematical construction, we’ll never be able to create an original painting; machines cannot create, just calculate, but their calculus may disguise itself terribly well as spontaneity (Chappie [2015] is a similar philosophical attempt, but it hideously degenerates into banal gunfire battles and cheesy humour). The astonishing ending is an eerie, unsettling outlook on the countless possibilities of future robots’ will, both in terms of appearance and attitudes.

Another recent nice (and tasting nostalgically “old-fashioned”, also in the soundtrack) film about robots is The Machine (2013). Well, it is not as deep as the one above, because there are way too many bullets, but I think it is worth a look, because the love story is gradually (fortunately) blended by the birth of the unequalled superiority of the mechanical “race”.

Her (2013) is about (romantic) relationships with machines, too. It is dreamy, sometimes unreal, suspended on many questions about our blurred-by-routine identity and desires, and it makes you feel like you just resurfaced from a long apnoea. I know, it is kind of a love story, but deals with a not yet existing technology, so… sci-fi, somehow. Actually, having sex with androids will be much easier than discussing about anything with an AI, I guess, because programming such a complex robot mind is still a dream.

|

| Ok, I confess: Her moved me to tears. This doesn't mean I wasn't intellectually stimulated... However, an other important element of this film is the solitude and affective isolation caused by a working-based lifestyle. Well, the Western one. Isn't this the reason why we always feel like messaging someone?... |

But this film shows you how deeply human feelings are affected by the temptation of an “abstract” relationship - namely, the ones we pass through without touching nor seeing anyone. Technology already created long-distance love stories, and they will grow probably more and more important in our life, since the mind of modern human beings cannot really remain in the same place for long time. We can love many people or virtual people, in many ways, from many places, and I think this film shows you exactly how difficult is going to be for us to feel just humans with bodily limits - and the worst of these limits, probably, is the need of being considered unique. Watch it; don’t worry, it’s not just romance.

Of course I must not omit Transcendence (2014), and I guess it pretty much explains why by itself. I should add that yes, maybe some aspects of the technology shown in the film are a little exaggerate, but the idea (the art) focuses on the fact that the essence of humanity, at the end of the day, is establishing strong ties with other people. The protagonist achieved the (maybe) last stage of intelligence, that is a spiritual/digital flux of data influencing reality without any bodily restrictions, and, by doing so, nothing was left to him but the interaction with the woman who knew him the best.

| |

| Transcendence, of course, is much more than a man vs. machine film. The protagonist, by transfering his personality to a digital system, becomes not just immortal, but almighty, managing to control, heal, improve every living being he's interested in with advanced nanomachines. Basically, he can enhance other people's humanity... and still love, wow! |

The very core of the film is showing us, of course, what are the perspectives of science about death. Again, the personality backup which allows the protagonist’s life not to end (well, to end just physically) is still a dream; I don’t know if we’ll ever be able to reconstruct someone’s personality by using megabytes, but this film, for sure, depicts majestically our yearning for a more and more abstract existence - because our future is abstraction, deal with it.

Something similar had been shown by, among many others, eXistenZ (1999), Cronenberg’s famous masterwork which focused more, anyway, on the sublimation of humanity by games and virtual achievements, and about which I could write for hours. So, I’d better stop now.

I must absolutely add The Congress (2013), an Israeli animation/sci-fi story with a hint of delicious retro design style. This film is an amazing journey in a dystopian world (well, just a large area of a world) where people use a special drug in order to evade reality, suppress sorrow and create their own personal crazed perception. Yes, I know: Huxley - although in this moment I’m also recollecting, while talking about recent stuff, We happy few (2016), a fascinating, dystopian video game; but the difference is that The Congress people can do and become anything by affecting their brain like that, from riding a raging bull to turn into Jessica Rabbit.

The protagonist, Robin Wright, playing as herself, not able to keep working since cinema industry can use digitally, and at will, the actors’ appearance, chooses to try this drug in order to find her lost son, who suffers for a syndrome destroying his senses; this lets the animation part begin, putting an end to the “real” Wright's performance. Thanks to the special substance provided by a huge corporation, nobody in the animated zone remembers about the “normal” perceivable reality, which is slowly decaying. Tastes, colors, bodies, smells, everything is an artificial stimulus, with no limits to variations.

This film is delicate and unsettling, extremely creative, aesthetically crazy, with long silent moments, and focuses on the uniqueness and rarity of strong feelings saving human life from boredom and nothingness. Where everyone looks like someone else, only people loving you remember who you are. More than that (and here is the core), The Congress tells us our reality is more and more made of cerebral stimulus and less and less of material objects. Appearance and personal experience will be just a matter of fantasy. We are our brain, and science keeps trying influencing its electric activity in order to gain an enhanced reality. We will be able to live, basically, without moving. Of course you may think about Brazil (1985), Matrix (1999), Wall-E (2008), Surrogates (2009), and many other deep works, all of them converging to the same fear/attraction towards cerebral life. In general, The Congress is one of the best animation movies I’ve ever seen.

|

| Zero Theorem (2013) is disturbing, grotesque, melancholic: of course, because it is directed by Terry Gilliam (Brazil [1985], 12 Monkeys [1995], The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus [2009]). I have to confess I'm not crazy about Gilliam's morbidity, but I found this film tremendously "interesting", since the protagonist, stuck on a chair, working relentlessly with his computer and recollecting some sweet memories from time to time, struggles desperately against the impending Nothing. Doesn't this depict our actual condition? Doesn't this concern all of us?... Yes, that's art. |

Obviously I could make some more (not many) examples. There are, and there will always be, many ways to talk about the human condition by means of cinema; but, as already said, I think nowadays sci-fi is the best instrument to achieve this goal - and that’s nobody’s fault, it's just a fact. Apart from the reasons I mentioned above, I think this is also due to the fact that society changes faster and faster, and that technological/scientific settings are the only ones which can keep pace with this frantic development.

Many of these settings, obviously, are quite banal or not very detailed (In time [2011], Elysium [2013], Divergent [2014]... way too many others), and of course I didn’t say sci-fi proved to be immune to degeneration, commonplaces etc. But I think (I hope) that the films I mentioned have good possibilities to become classics - at least, to live for long in our memories as good examples to cite while we'll be talking about art in the early 2000s'.