I'm sure many thoughtful people have already told you that we're surrounded by pictures; there are probably too many pictures. Pictures of any kind and source claim their dominion on information. Words are probably too many as well, too "flickering", and perhaps we don't focus on them enough - also because of the fact they don't focus on us themselves. But pictures are immediate, often staggeringly immediate; most of the times, probably, people improvise as photographers because an overwhelming information culture leads them to share their visual impressions at any cost, in a narcissist (a little onanist) struggle to feel special.

As a lover of literature, I am frequently bored by words myself, especially by novels, because narration does nothing but repeating the standard, predictable structure of everyday life and language - at least, most of the novels whose covers are in the windows of the bookshops. No, I don't think I'm picky; I just think putting words on a page with a correct syntax does not mean being a writer. The way we surround ourselves with words shows so clearly the unsuitableness of our language; we repeat the same language structures all the time, even in a creative context, because we need to make reality, to some extent, still recognizable.

As a lover of literature, I am frequently bored by words myself, especially by novels, because narration does nothing but repeating the standard, predictable structure of everyday life and language - at least, most of the novels whose covers are in the windows of the bookshops. No, I don't think I'm picky; I just think putting words on a page with a correct syntax does not mean being a writer. The way we surround ourselves with words shows so clearly the unsuitableness of our language; we repeat the same language structures all the time, even in a creative context, because we need to make reality, to some extent, still recognizable.

|

| Guy Debord (1931-1994), in his famous work The Society of the Spectacle (1967), talked about mass society's need of being fed with pictures in order to be kept awake for the "spectacle", a non-life created by capitalism to be in charge of workers' desires and needs. Spectacle, which means the industry of advertisements, entertainment, information etc, somehow took over the ancient role of the Church in giving people a vision of an inconceivable world of possibilities (what you can buy, the place you can go on holiday, the new technological devices, the virtues and enterprises of leaders and so on). Among the many spectacular features, he also talks about the central role of picture: "Where the real world turns into simple pictures, simple pictures become real beings, and effective motivations to a hypnotic behaviour" (18; translation is mine). |

But this post is not meant to be whiny and nostalgic, not at all. Fluid, ever changing, less and less definable, society is not very likely to be described by words, that's all. This is not to be necessarily considered a drawback of our frantic life, but a matter of fact; an interesting matter indeed, because our life goes much faster than our verbs and adjectives, for the first time in human history. The social media empire (even if it still has way too many emperors fighting for the throne) replaced, for the most part, not just our judgment, but our expressiveness.

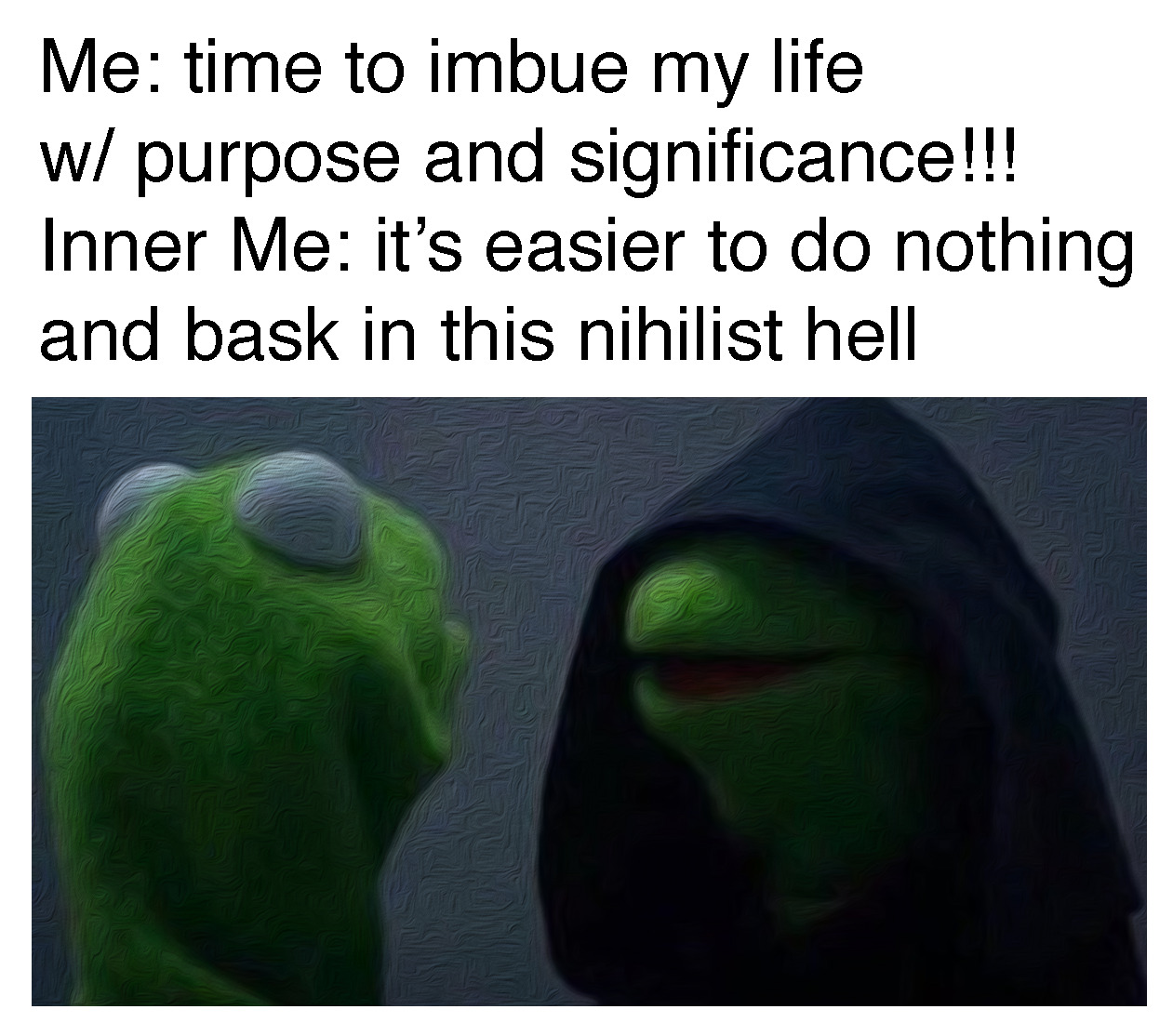

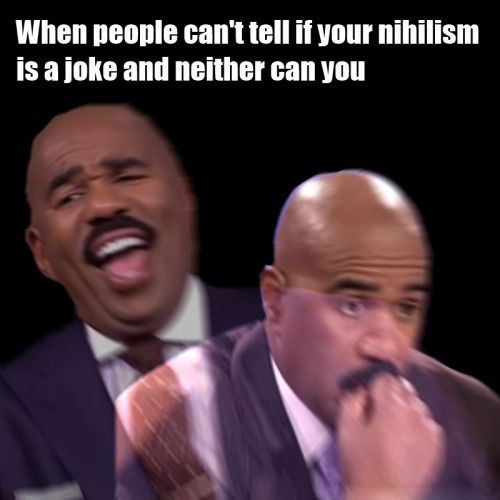

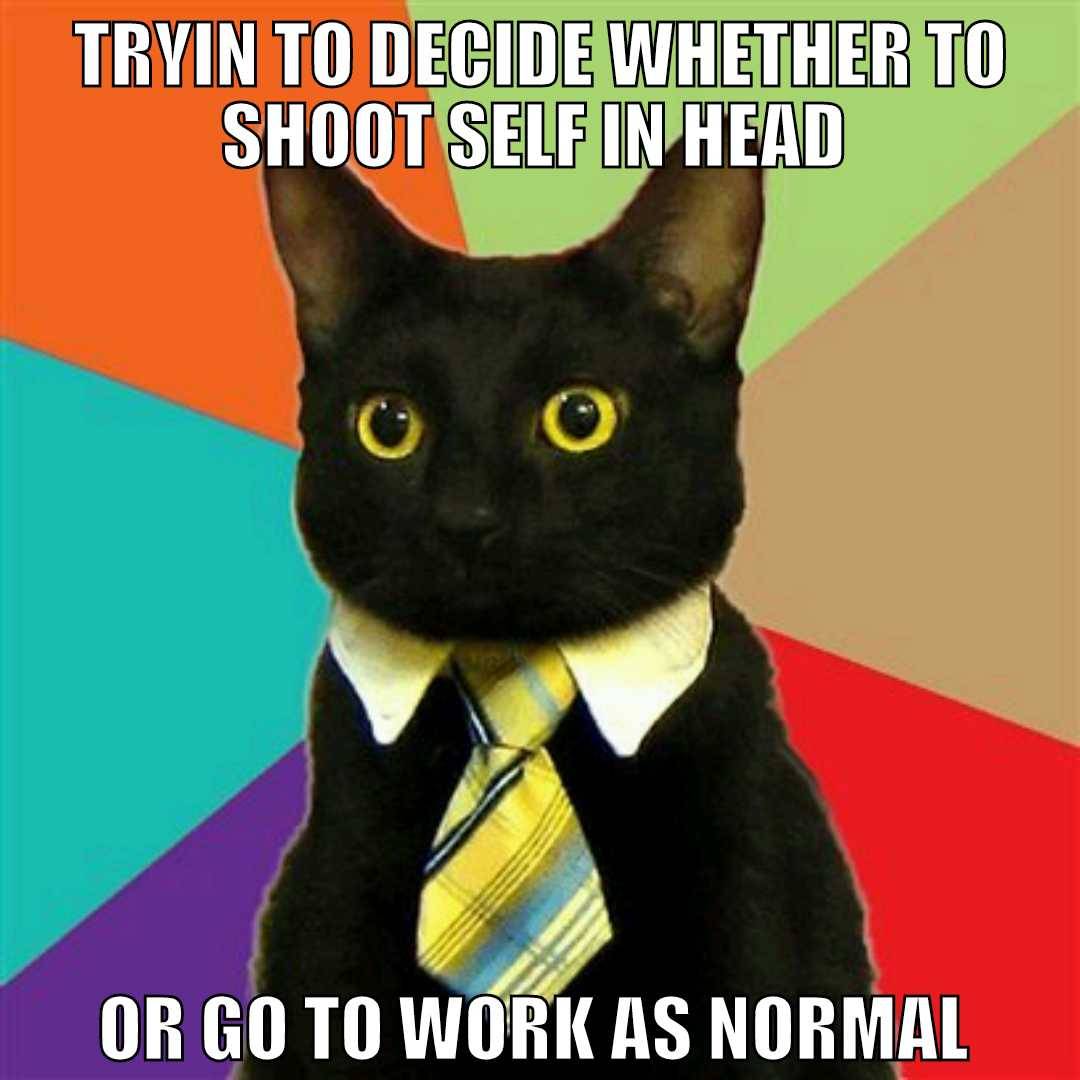

That's why, I think, memes (I am talking about Internet memes), among the most recent forms of communication, are the most likely to become viral: the social channel, the combination of picture and word, creates an immediate ironical message, mostly funny, which can be shared straight away. The phenomenon of meme should be analysed in light of the fact that most of the times we need something to be "viral" before deeming it worthy of our attention; and yes, I think this is partly a pity, because we focus more and more on stupid things, which are, that's another matter of fact, the most popular.

That's why, I think, memes (I am talking about Internet memes), among the most recent forms of communication, are the most likely to become viral: the social channel, the combination of picture and word, creates an immediate ironical message, mostly funny, which can be shared straight away. The phenomenon of meme should be analysed in light of the fact that most of the times we need something to be "viral" before deeming it worthy of our attention; and yes, I think this is partly a pity, because we focus more and more on stupid things, which are, that's another matter of fact, the most popular.

|

| I guess you've already seen this painting in some articles or books about mass society; so, I don't have much to write. The fact is that Christ's Entry into Brussels in 1889 (1888) by James Ensor (1860-1949) always looked like one of the best sociopathic pictures ever to me; is it just me, or there's something monstrous in this crowd? All those soldiers in rows, all those grotesque masks not very interested by the arrival of the Messiah, all those people trying to have a good time in such a suffocating place made me think that the painter was unbearably tired of masses; given the script on the top, I'd say this work may be called Social Network. |

Many memes are about a specific category of things or people (Game of Thrones, Donald Trump, football), and sometimes they cannot be understood by every person; Facebook pages, of course, are often created just to share memes, and Facebook memes pages are probably the most popular at all. In particular, there's a type of memes I am, I confess, really into, which lately became very fashionable; its appeal is probably the main thing convincing me not to leave the social media world. I'm talking about nihilist memes.

|

| From the Nihilist Memes II Facebook page. This is an example of the cynism I and many other normal working people probably cannot live without. This popular page often talks about children's destiny, since children's happiness and possibilities in a brand new world is exactly what helps most of people not to think about the nothingness of the universe. We make children for ourselves, and nihilism comes more from acceptance than resistance; life itself, having goals, procreating etc. are an act of resistance. |

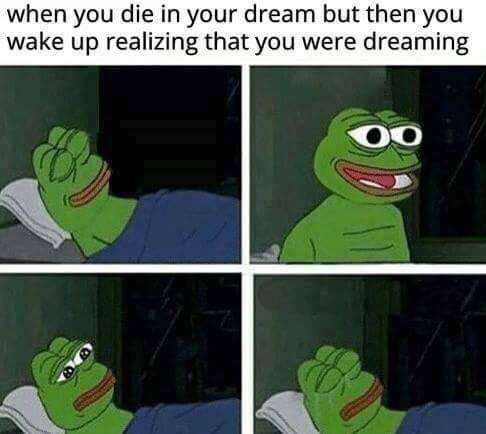

I am sure nobody expected memes to become so popular as a reaction to the bitterness of life; starting more than ten years ago, cynical, sarcastic, often exaggerated memes about the emptiness of the universe, the urban life paranoia and various inner wrestlings spread through the Internet via every social media, probably starting from 9GAG and 4chan, and the birth of a Facebook page called just Nihilist Memes in 2014 made them even more various and sophisticated. I really enjoy the irony these memes express, especially about the way nihilists (but they often use this word as a synonym of depressed people) have to deal with the rest of the world. An exorcizing wit considers death to be the main reason of strong human passions, including, of course, the instinct to reproduce.

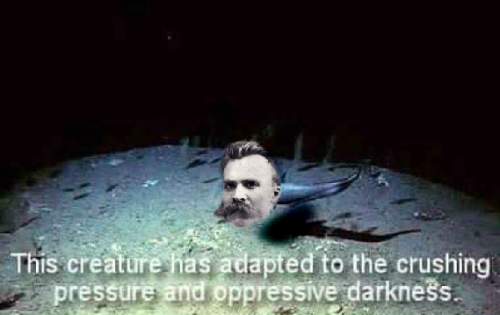

Death is often seen as a liberation, and the tragic irony about the very few probabilities we have to pursue "real" goals (nothing is real, because we cannot but delay temporarily our appointment with death) is often, and willingly, excessive. The end of philosophy as a systematic study of reality is shown through the means of sarcasm about past philosophers' failing definitions and studies, or through pictures of Nietzsche, the great destroyer of illusions.

Now, dark humour is not a new thing, that's for sure, but I think there's something a little disturbing in the way we, as inhabitants of the globalized boredom, repeat to ourselves that everyone and everything dies; disturbing, mostly because very often, instead of living, we just attend life (as you are expected to do in a society of spectacle), and wait for things to pass on the screen in order to get some laugh or distraction out of our ridiculous human tragedy.

Our common conception about death being usually impersonal and scary, we have to be ironic at any cost, especially through popular video games, films or cartoon pictures, that is, recognizable and somehow appeasing pop culture fragments. Even Super Mario can remind us we are nothing and will always be nothing; Spongebob's large smile is often used by these memes as a maniacal laughing about horrible contradictions of life; Rick and Morty's famous character Mister Meeseeks became a paradigm of an urging will to die, in order to end the incessant existential suffering. As I've heard once in a 2008 film by Paolo Sorrentino, irony is a medicine you get not to die, and "all medicines you get not to die are atrocious".

As I said, many times I enjoy nihilist memes, and I really appreciate the fact that the art of memes managed to make us laugh about topics people are usually scared of. But I also think that the astonishing popularity of bitter existentialist problems depicted by funny pictures can lead people, as usual for most of Internet features, to overlook life itself. By striving to find a distraction, something to focus our sight on while we drag ourselves to work and back home, somehow we overlook life, we miss its depth and its complicated beauty, we get to pessimistic conclusions without really staring into it; short story short, being a nihilist became far too easy, and everyone can be ironic about depression without even imagining what depression is.

Memes can be misleading, and I often notice that people feed on memes in a worrying escapism. Irony does represent a way not to succumb to sadness, of course, but maybe we have learned this art so well that we forgot how to appreciate the real life (I mean, outside the spectacle) in the serene awareness that it is just a transitory state of matter. I have the feeling we spend more time complaining about the void than living according to it, which means we shouldn't embrace the emptiness of life without seeing the powerful, contradictory mystery of life itself - we never see dead people but in fiction or in the news, for example, and we're aghast, mystified every time someone tells us they're unsettled by this economy-based existence; we don't know how to deal with real problems, but we always talk about anxiety, fear and suffering. Anxiety is definitely one of the most common keywords in memes. Everyone needs to talk about anxiety, mostly due to trivial problems. Nobody can afford to be considered normal; everyone wants to show off as a troubled person.

I am not the one who talks about hunger in the Third World in order to minimize depression and psychic diseases, but maybe memes are too often a way to wallow and not to think about how big problems-free our little First World place is, at least for now. We can realize the void, and this gives us the power to overcome any poisonous illusion, religion, blindness; even existentialist pain can be a nice reason to visit more places, finish reading War and Peace, maybe help people who cannot afford to think about deep things.

The fact is, depression is not nihilism. Given the fact that suicidal tendencies became so popular, maybe we should reconsider the nature of our feelings; are we truly sad, or are we just looking for attention? Are we really pessimistic, or do we just want to look interesting? The fact that nihilism became something so easy to share maybe made nihilism itself an impersonal attitude, a fake approach to life. A depressed person, on the other hand, wouldn't need irony, and maybe there are no proper reasons to make so many jokes about suicide.

As explained in Guy Debord's masterpiece, The society of spectacle (1967), the more unsatisfying life grows, the more powerful spectacle becomes; so, what I find eerie about the rise of nihilist jokes in the past decade is the fact that we keep staring at a screen which tells us life is bad because we are put in front of a screen (Black Mirror is a perfect example in this sense). Basically, since we cannot get satisfaction out of an economic system which puts us at the edge of existence, we cannot but laugh at ourselves bitterly through the means given us by that system itself.

We struggle for new expressions for our unsatisfaction, because this unsatisfaction is the only thing making us feel alive. We are so accustomed to the fact life is competition and harshness and money-based ideas that we mostly give up looking for a balance outside the home walls; it's exactly the same paradox making Netflix and videogames almost pathologically necessary for so many people (Debord [217-219] talks about this obsessive need of fiction as a schizophrenic reaction to the fear of being absolutely unnecessary].

We hardly experience death as a collective feeling, but we strive to see death in memes and fictions; we hardly find the will or the time to read philosophy books, but we have to put Kierkegaard and Sartre in a funny picture. The utterly ahistorical social context we struggle for money in persuades us to look at history as something ridiculous; only this context could generate this type of dark humour, and an ahistorical nihilism we can use to justify our fear of life. Augmented reality is probably the best way to make nihilism unauthentic: our impressions and feelings are so artificial that somehow even our fear is.

Memes are not a bad thing, neither a good one. They're an interesting cultural phenomenon, and I like talking about it as such. As you maybe already know, this word, derived from a 1976 Richard Dawknig's famous book, means "something which can be imitated, replicated" (Greek "mimema"); there couldn't be a better definition for our disquieting misconceptions about culture. Being entertainment a mean of survival in an urban life which makes us feel meaningless, knackered and inadequate (the struggle to survive never stopped, just changed its selection methods), I totally understand why we need pictures to be countless, immediate, simple and possibly funny; I just hope that this never-ending hunger of shallow information will not persuade us to overlook words and pictures that maybe are still worth something more than a joke.

We are turning into memes; our life is a meme, where we repeat and do and joke about a standard stock of situations. A countless horde of "When you..." memes makes people laugh at and share utterly banal feelings and situations anyone could feel mirrored in. We need to clap our hands to ourselves, continuously. We don't separate our judgment from the media surrounding us, and we feel we should live somehow, but we don't remember how.

That's why, all my aforementioned fears notwithstanding, I decided that nihilist memes are probably the most interesting, or better, the least shallow memes you can find. At the end of the day, without pretending we are in charge of our lives, we managed to create something funny about our tiredness: there are no more illusions to fiddle with, and our mortality is nothing staggering anymore. The "system", that is, the production process, has already won and always will, so we find no reasons not to make light of our parcellized life, whose goals cannot be but money-oriented.

The main drawback of all of this, as I said, is that everyone can play depressed, philosopher, deep, and every time you would like to say something more than "life sucks", you have the feeling someone is already making a meme about you; you are old, you are boring. By "memezing" the emptiness of life, we make it less and less philosophical, in the sense that we struggle less and less to enjoy it.